The first time I remember hearing the joke, I was on the second floor of a block of flats in the Cairnhill area of Airdrie. A young boy, sitting warming in front of a 3-bar fire. With the smell of pan-breid toast in the air, I told my gran that I wanted to be a singer. She asked me if I knew how to get to Carnegie Hall. I didn’t know what a Carnegie Hall was. Perhaps it was in Edinburgh, I remember suggesting. To a bemused pre-teen, she replied practice, practice, practice. Huh? Later in life, I got the joke but I feel it is always better when subverted. In Demetri Martin’s telling, it’s practice, practice, practice… then make a left.

Practice makes perfect, so we’re told. As a lazy teen playing noisy guitar, I rebelled against sensible notions as, oh, being good with the instrument. No need to practise, then. Later in life when I began to play the piano, times had changed. I understood the importance of practice, compounded by the indisputable fact that I wasn’t particularly good.

Making an Effort

Despite what some may say, street photography is not easy and it takes years of determined, deliberate practice to make it look like it may be. Henri Cartier-Bresson’s quote that your first 10,000 photographs are your worst sits in eerie similarity to Malcolm Gladwell’s assertion that one needs 10,000 hours of practice to achieve mastery. Weathered street photographers know that in any given year only a handful of photographs made will be special. I manage 10 to 15 true keepers each year and if I am lucky 1 of them will be a truly special frame. Of course, I achieve nothing if my camera sits on my desk, and I’m indoors playing the latest Spider-Man video game.

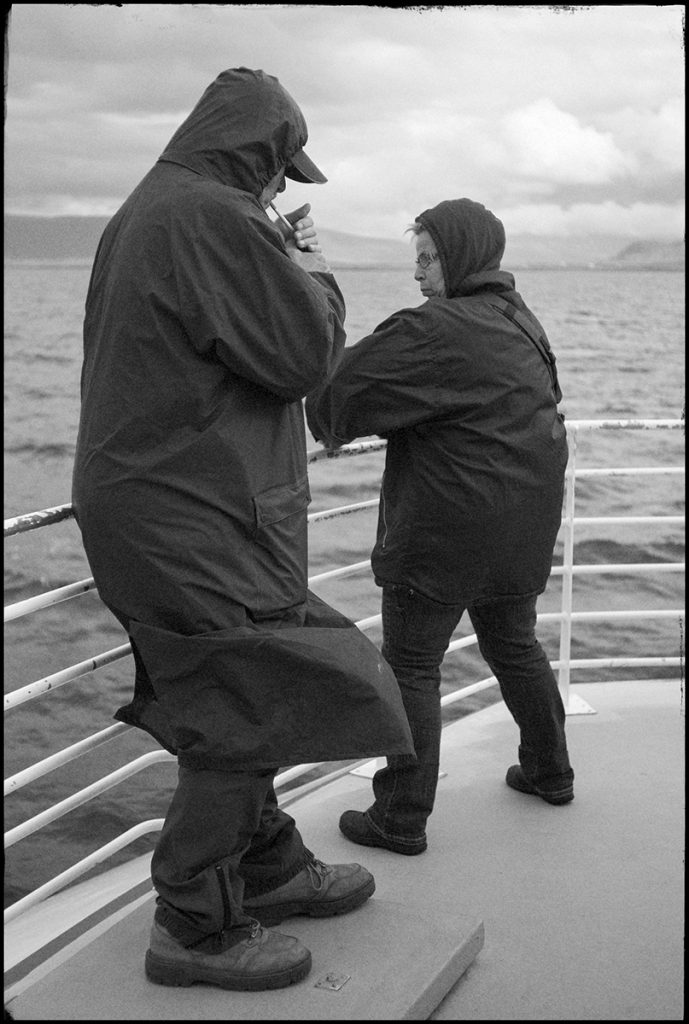

To practise street photography, one must walk out of the apartment door and become immersed in the world found there. Here, the street photographer learns by doing, by walking the many kilometres, wearing down the soles of the shoes, and by training the eye to see, and the reflex to react. Commit to the practice of street photography and whether rain or shine, throw the camera over a shoulder and get out there.

Building Experience

A musical instrument is practised before performance, whether alone or with a group. Issues are ironed out before taking to the stage. In street photography, the practice is done on the run. As such, all perceived failure can be treated as the product of practice. To critically evaluate the pictures after a day out photographing is a crucial way to learn what went wrong and to find the best strategies to correct it the next time. If a poor composition was chosen, how may it have been improved? If timing was off, would a quicker reaction, or a delay have made for a better photograph? Was the shutter speed too slow? Was the aperture too wide?

New Horizons

With practice and review, such things become second nature, and some choices can be left to muscle memory. With repeated practice, the camera can become an extension of the photographer. Natural in hand and when brought to the eye – familiar and used without breaking concentration. Finding this comfort with the camera is made easier when beginning by choosing 1 camera and 1 fixed focal length. Familiarity with a camera avoids any fruitless search for dials or settings in the heat of the moment. Sticking to 1 focal length, the boundaries of the frame become instinctive. Even without the camera, I can intuit a 50mm frame.

As those rhetorical 10,000 worst photographs are slowly spent, so much can be learned by experimenting and practising on the street. Take chances, make bad photographs, if only to see the limits, or lack thereof, of a certain idea. There is no substitute for being present, with an innate curiosity watching life unfold and releasing the shutter when something feels interesting. Though it can be tempting to stick to areas of the city where success has been found, overcome that temptation to push outside the comfort zone and mix those happy hunting grounds with new horizons.

Growing Confidence

A vital benefit of practice I have found is growing confidence that pushes me out of periods of imposter syndrome. I have some experience and yet, I still find myself struggling with the fear of not being good enough, or a fear of confrontation. These anxieties are more pronounced when I have had a longer break from making photographs. After some afternoons out in the city, pushing myself to stretch the elastic of my comfort zone, I find the practice has given me back the confidence that leaked out, like the air from a bicycle tyre.

It would be silly to imagine that a camera can be left on the shelf for months, and then the rusty street photographer can hit the ground running. With some experience, and a hiatus of over a decade, I can say without fear of contradiction that this isn’t the case. Street photography does take some figurative warming up. I would say it took about a year for me to exceed the level I had left behind before moving to Poland.

In microcosm, this works in much the same way on a daily basis. While it may happen, I don’t expect to make my best photographs immediately upon leaving the flat. It can take some time to build momentum and to find the rhythms of the street. Somedays it is easier than others. One afternoon it may be chaotic, on another it can be prosaic. Finding and matching that pace can take a little practice.

Directions?

This feels like a lot to return to the simple truism that to get to Carnegie Hall, it takes practice. Or in the case of street photography, we can think of the alliterative words of Magnum photographer, Bruce Davidson when he described what it takes to make a great photograph: Passion, persistence, patience, and, I would add, practice.