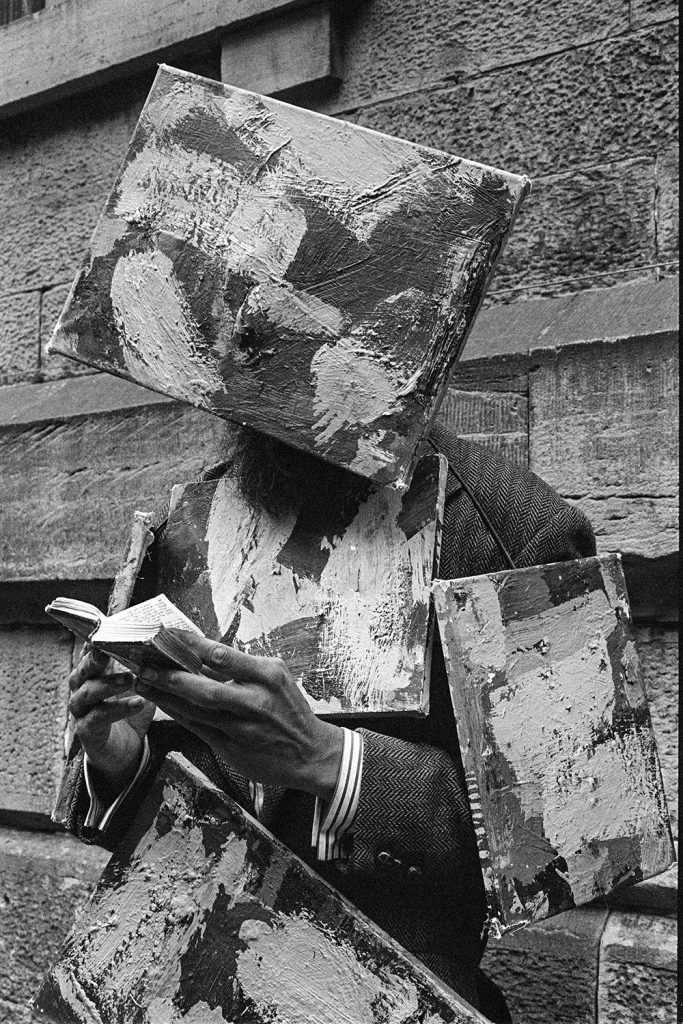

As the 2 rolls of film just developed, hang on a clothes hanger, dripping over the bath, I take quick, rushed pictures of 3 frames at a time on my phone. Once finished, I close the door, turn off the light, and leave them there ’til morning. Impatience demands I flick through the rough images on my phone. For the first time, I see what I’ll have to work with in the morning. First impressions? An abundance of mediocrity, with one or two that stand out from the crowd. Occasionally, I may see something that catches my eye, like the reflective hologram of a ‘shiny‘ in a packet of Panini stickers. That rare frame: The keeper!

Realistic Expectations

Subjectivity and personal style are crucial in growing as a street photographer and developing an improved sense of what makes a good photograph rather than an average one is vital. When we start out making street photography, everything is fair game, from the esoteric to the mundane, from the unique to the cliche. As one grows, it is important to discern which is which. What makes a good street photograph? Would the frame have been improved had the shutter been released a second earlier, or a second later? It is important to set realistic expectations. Even the masters of the craft will come home after a day in the city with a generous collection of nearly-theres, and also-rans. Being able to understand and see the difference is what sets a good street photographer apart from the ordinary. Quality really does trump quantity and editing a day’s, week’s or month’s work to choose only the best to show the world is what sets an aspiring photographer apart. A truly great photograph is not a regular occurrence. Not even for the best.

Street photography is Not Easy

While masters such as Cartier-Bresson, Winogrand, and Frank make it look effortless, street photography is not easy. In truth, I have a number of photographs I am very happy with, however, I only have a handful that I feel are exceptional – and that is normal. If you step out onto the street expecting to return with a roll of film that is all killer no filler, you’re in the wrong game, my friend. The contact sheets of the aforementioned masters disabuse us of that expectation quicksmart. When Alex Webb says that street photography is 99.9% about failure, it is that 0.1% of success that we strive for. Shyness, timing, poor composition, right-time-wrong-place, there are many challenges standing in the way of making that keeper, all of which can be overcome with practice. It takes experience to find a good perspective. It takes photograph after photograph after photograph to learn just when to squeeze the shutter. And even then, the vast majority of photographs we make will be humdrum.

When Failure isn’t

There is no substitute for hard work, for being on the street to make photographs. After a bad day, it can be easy to procrastinate and avoid returning the next day. It is tempting to think of all those disappointing frames as a waste. Not at all. Though counter-intuitive, failing time and again is the best way to discover what a keeper truly is. Understanding this and learning to embrace the process is a path to better photography and to avoiding frustration and anxiety. Learn from others, of course, but accept mistakes, missed photographs, or average work as prime opportunities to improve. Often the difference between a strong photograph and an average one is timing. Anticipation becomes key, then tripping the shutter as all elements fall into place. Cartier-Bresson’s famed non, non, non, non, oui! At other times, it is not timing but footwork that lets us down. A quick step forward, or a sidestep to the left would have found the moment in a well-organized rectangle, but instead, it’s just not quite right. Be critical of your own work. Ask why the photograph does not work, and what could be done to improve it next time. Then go do that.

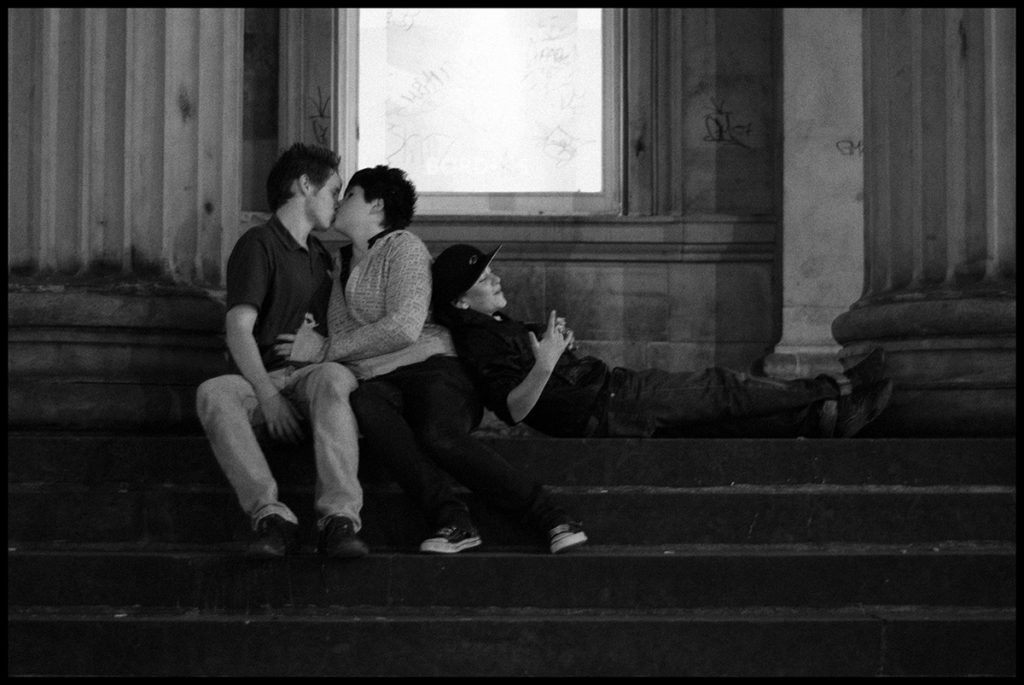

Finding the Keeper

Often, when reviewing my negatives or contact sheets, I see a photograph that doesn’t work. The idea does, but the elements in the photograph don’t sit well together. These are my nearly-theres, and it is especially tempting to include them in an edit, after all, the intention was good. For years, I would consider them good enough. It was Richard Kalvar, in fact, that made it clear to me that intention is irrelevant if the result is a poorly organised rectangle. There are numerous excuses why the photo just isn’t there, and it can be hard to accept but accept it we must if we want to improve. My partner has grown used to my heavy sigh of resignation when I realise a picture I was excited about just won’t sneak through my edit. It is all the more satisfying, then, when a gem of a keeper appears. To see among the many photos, both pleasing and disappointing, the one that screams Nailed It! is some reward for the patience, persistence, and continued growth in the journey towards becoming a better street photographer.