Spring is in full swing and the world is emerging from beneath its weighted blanket. Street photography doesn’t stop in winter, but it is certainly more challenging when people are cosy by candlelight in the early evening gloom than out enjoying the city.

March was just beginning when a parcel arrived. My Leica M3 returned after a lengthy spell at the workshop for a CLA. My M6 is now facing a spell on the sidelines and with it, its light meter. Taking its place, occasional spot-checks of a handheld meter, and the famous Sunny 16 rule.

As such, it seemed like as good a time as any to touch on ways the Sunny 16 rule can be advantageous to street photographers using analog or digital cameras alike.

The Sunny what?

The Sunny 16 rule has its foundations in the law of reciprocity. Put simply, to maintain the same quantity of light if, for instance, the duration of exposure is increased by slowing the shutter speed by 1 stop, then the intensity of light must be reduced by narrowing the aperture by the same distance, 1 stop.

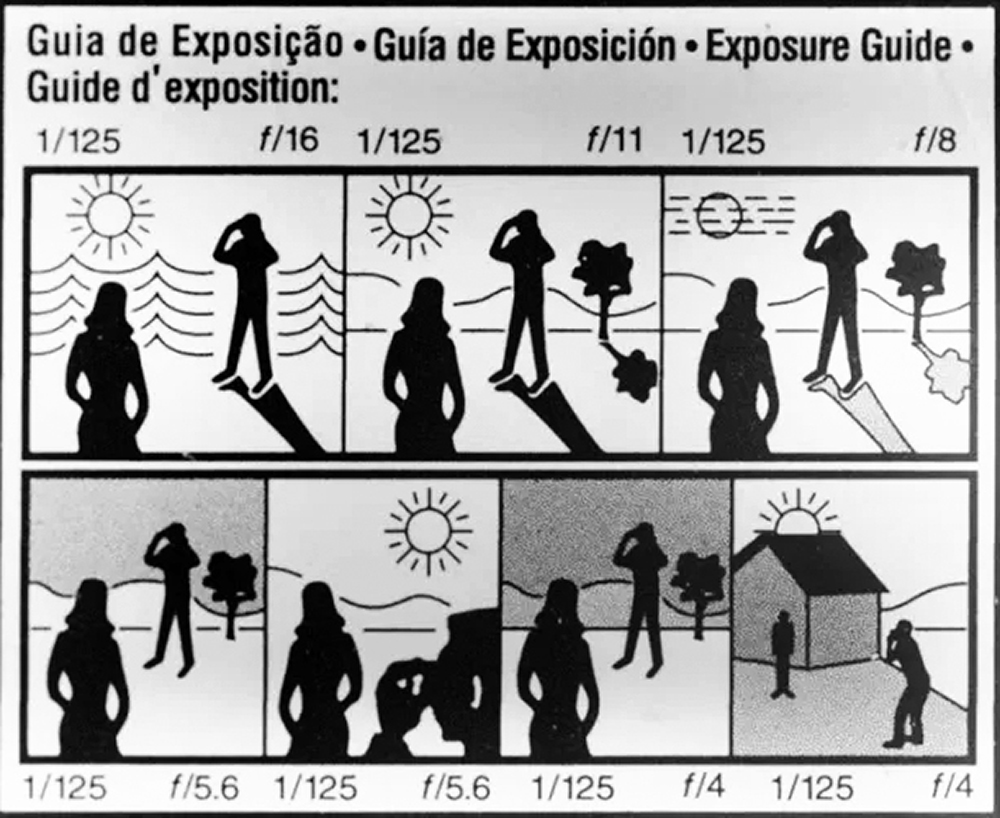

Early photographers discovered that when shooting in intense, direct sunlight, they would achieve consistent, correct exposures by following a simple rule: Set the aperture to f/16 and choose the closest available shutter speed that matches or is closest to the numerical value of the ISO.

For example, using Kodak Ektar on a Leica M3, the ISO is 100. In direct sunlight, the aperture should be set to f/16 and the shutter speed to 1/125s for an estimated correct exposure.

Another example may be, using Kodak Tri-X at box speed in a Leica M3, the ISO is 400. In direct sunlight, the aperture should be set to f/16 and the shutter speed 1/500s or 1/250s. When shooting film, it is always better to opt for more light than less so the latter is the better choice, particularly in countries further from the equator where sunlight is less intense.

But, you live, say, in Scotland, and direct sunlight is a myth!

The Sunny 16 rule offers a place to begin to estimate a correct exposure. Let’s be thankful for the generations of photographers who have come before. Those who experimented, and suggested further adjustments for different weather conditions.

For sunlight diffused through broken clouds, the aperture should be opened by 1 stop and set to f/11.

On an overcast day with light clouds, set to f/8. For overcast, heavy dark clouds, open 3 stops to f/5.6.

In deep shade, or at sunset, the aperture can be opened up to f/4.

To remain at f/16 on a light, overcast day, rather than increasing the aperture by 2 stops, use the law of reciprocity and instead reduce the shutter speed by 2 stops.

Alternatively, to use a different shutter speed than the rule suggests, again use the law of reciprocity to dial in a correct exposure. When using Tri-X as above, instead of a shutter speed of 1/250s, 1/1000s is required, perhaps to catch the flight of a bird. By reducing the duration of the exposure by 2 stops, the aperture can be opened up from f/16 to f/8 to reciprocate.

The Sunny 16 rule provides a starting point. The photographer has the final choice of settings for exposure.

How does the Sunny 16 rule benefit street photographers?

Why use the Sunny 16 rule at all?

Well, there may be no choice. For instance, no Leica prior to the M5, introduced in 1971, has a light meter. Indeed, few cameras of a certain vintage will have a light meter. A handheld meter or a hotshoe-attached meter can be useful, however, they take time to reference and set the subsequent exposure. In street photography, that may be seconds – and the photograph – lost. Even when using my M6, I may run out of the battery powering the meter. If I’m out for the day, it’s useful to have knowledge of Sunny 16 with it’s quick and easy exposure estimation to fall back on.

In-camera meters measure light reflected back from the subject through the lens of the camera. If the subject is predominantly lighter or darker than the majority of the scene, this may skew the measurement. For much the same reason, reflected light meters can struggle with challenging light and high-contrast scenes. Sunny 16, while an estimate, is theoretically akin to using an ambient light meter. It estimates the light falling on the subject, and isn’t affected by the subject itself or the scene. This is more likely to offer a more appropriate, consistent exposure. Especially in the street, where subjects come and go at pace.

THE SUN’S OUT. GET OUT THERE.

With some practice, it becomes easy to notice small changes in the light and adjust the aperture or shutter speed instinctively. Little time is spent thinking about exposure, instead more mental focus is used to look for moments to capture and frame them just right.

Metering in-camera is most often viewed through the viewfinder. Extra seconds with an eye to the ‘finder adjusting the exposure can alert all around to the presence of a camera. Instead, estimating exposure with the Sunny 16 rule, especially if used in cooperation with Zone Focusing, can temporarily turn your camera into a stealthy 1-click point-and-shoot.

Much like the aforementioned Zone Focusing, the Sunny 16 rule is a method of estimation, and a useful one at that. Some photographers feel comfortable using the rule at all times, and others – like myself – will whip out the handheld meter if there is a dramatic change of light. Nevertheless, using the rule successfully does take time, and there may be occasions when beginning to rely on it that the photographs will be over or underexposed. Keep at it. Practice breeds confidence. With more confidence, you can leave the batteries or handheld meter at home.