In my move from Glasgow to Warsaw, very few of my photo books survived. I sold off many at Caledonia Books on Great Western Road, in Glasgow, a combination of them being too heavy to ship, and an attractive source of emigration money. As an aside, having sold it to Caledonian over a decade ago and change, it was astonishing to wander into Oxfam Books on Byres Road just this May and find my sun-damaged copy of Aperture’s collection of Cartier-Bresson’s writing on photography and photographers – The Mind’s Eye. I bought it again. Obviously.

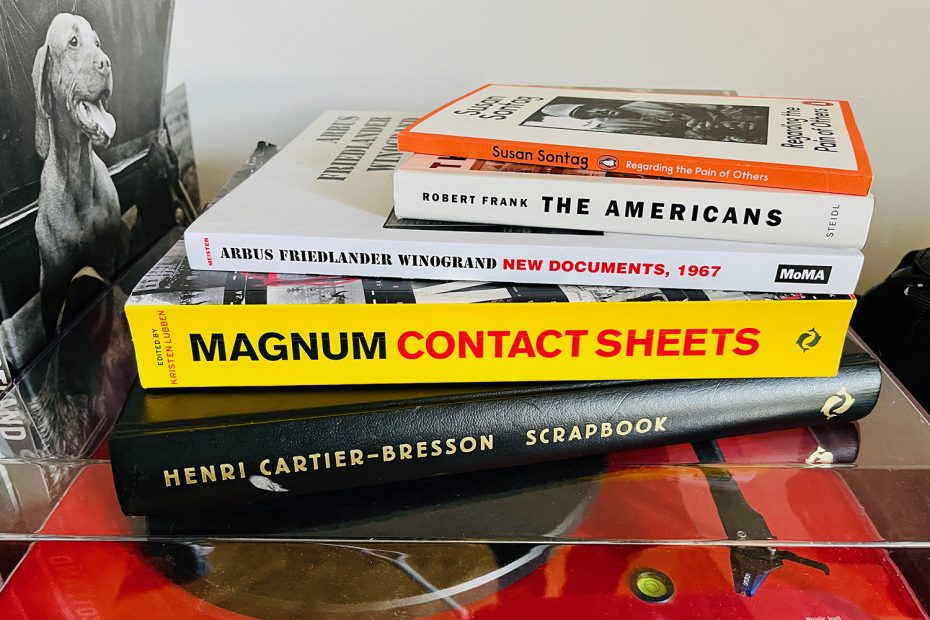

In the 3 years since I left the indie music industry and returned to photography, my library of photo books has steadily grown. Much to my partner’s dismay, it now occupies 5 squares of Ikea’s Kallax, and is expanding. Oh, Marta supports the library. It’s the Kallax she despises. New, bespoke shelving coming soon, I think. I have replaced many of the books I once let go, and I have acquired many others, and have no intention of stopping. Some are monographs, others are collections. Some are practical, others are philosophical. All are vital resources in improving as a photographer.

A Required Reading, not The Required Reading

In a recent, compelling conversation online, an opportunity arose to recommend some photo books. I offered a number of apposite suggestions. In doing so, I considered the photo books that street photographers must read. Required reading, if you will. In much the same manner that Simon Schama named his acclaimed television documentary series, A History of Britain, to indicate the subjective nature of his story, and that there are many other histories of Britain, entirely dependant on who you ask. This, then, is A Required Reading List for Street Photographers. Likely the first of many.

As I continue my studies, specifically on photography and art criticism, I will return to each book for a deeper dive, however, for now a brief guide to likely the first part of my required reading list for street photographers.

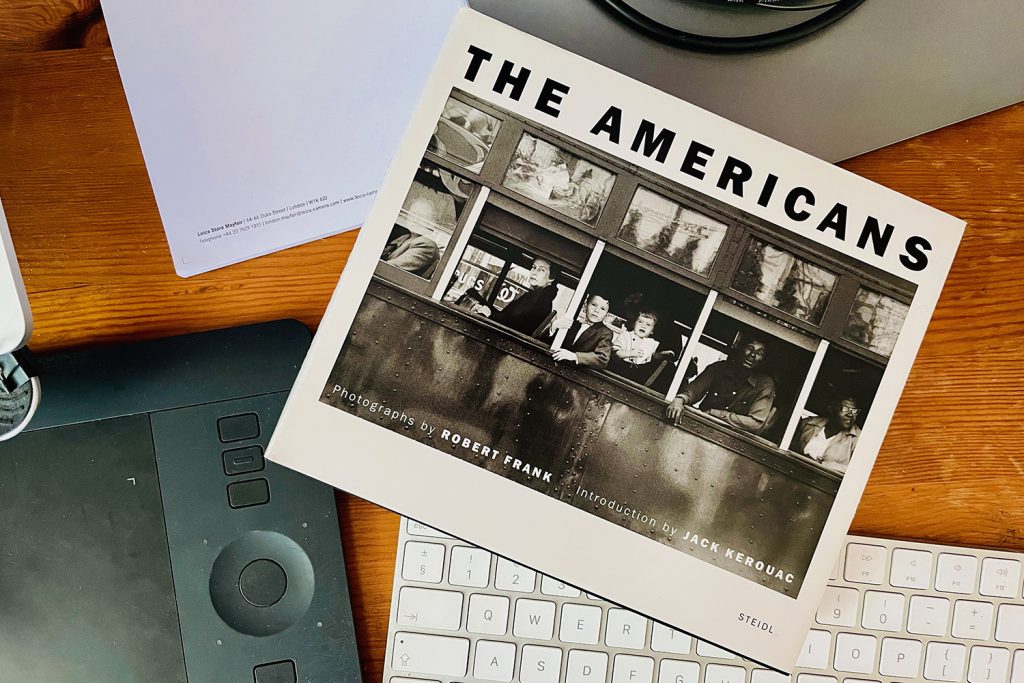

The Americans – Robert Frank (Delpire. 1958)

To write of Robert Frank’s collection of 83 photographs made while traveling across America in 1955/56, it is an effort not to tumble into a bad Kerouac imitation, writing as he does, with free-form poetic vigour, in the book’s introduction. The Americans received severe criticism on its publication. The contemporary magazine, Popular Photography, expressed contempt for its meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness. As an outsider, the Swiss photographer’s pictures held a mirror to the complex, nuanced myth of American exceptionalism, and many did not like what they saw.

Photographing with a Leica iiif, Frank was able to be so unobtrusive as to be invisible. Shooting on Tri-X and Plus-X, high speed for their time, he was able to take creative chances. With The Americans, Frank fractured the formality of the incipient practice of street photography, its trunk splintering with each frame, throwing shards of technical imperfection and unconventional form to pierce through the street photography of the next 65 years. With them, fly fragments of fascination, suffering, wry wit and observation, and of manifest empathy. To study The Americans is to take a formative step for any street photographer.

Read The Americans at the OpenLibrary through the Internet Archive

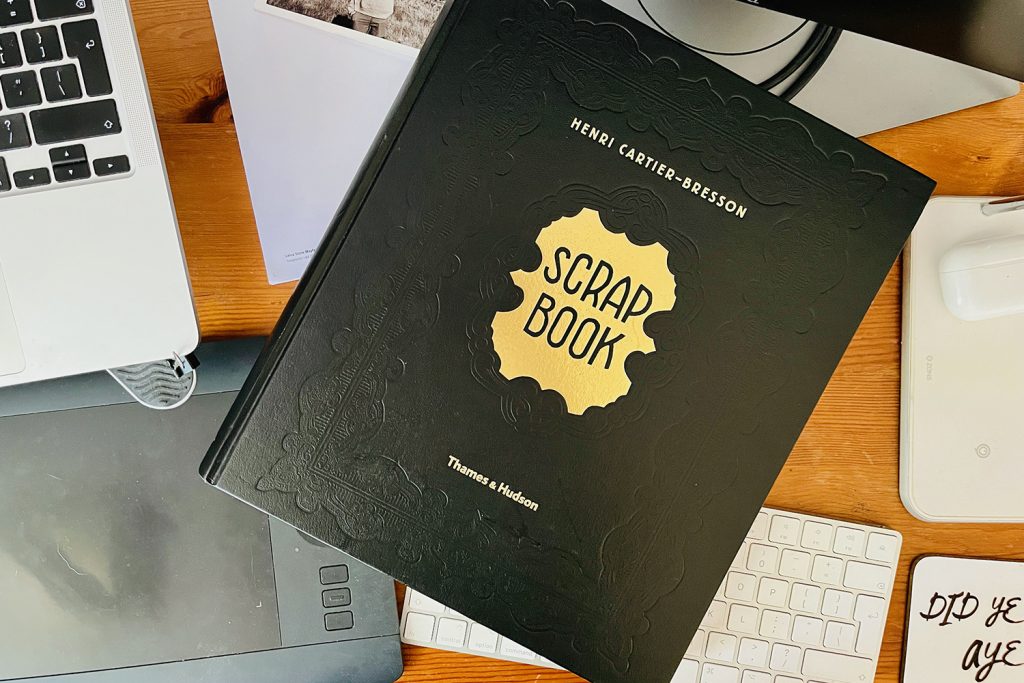

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Scrapbook: Photographs 1932–1946 (Thames and Hudson. 2007)

The story of French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Scrapbook is almost as legendary as the photographs themselves. During the war, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, believing the photographer had perished in a German prison, began to assemble a posthumous retrospective. Upon escaping his internment Cartier-Bresson was dismayed to discover he was dead, and delighted to learn of his retrospective, so much so he resolved to curate it himself. As a Surrealist, I imagine he revelled in the absurdity of it all. After the war, Cartier-Bresson travelled to New York with a number of prints, bought a beautiful, ornately decorated scrapbook, and created an album to be presented to MoMA. The exhibition was, of course, a success.

The photographs found in the scrapbook are restored with great care by the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson and are bound in a faithful recreation of the cover of the original scrapbook. Figuratively glued to the pages are many photographs that will be familiar, and a number that won’t. Present are his formative frames in early 1930s France, his travels through Spain, Italy, Mexico, the USA, the UK, and his many portraits of the time. The collection ends with his war-time photographs. Cartier-Bresson was to fill his pages with vivid, graceful geometry and articulate, playful humanism. The formal precursor to Frank’s seeming ambivalence to form.

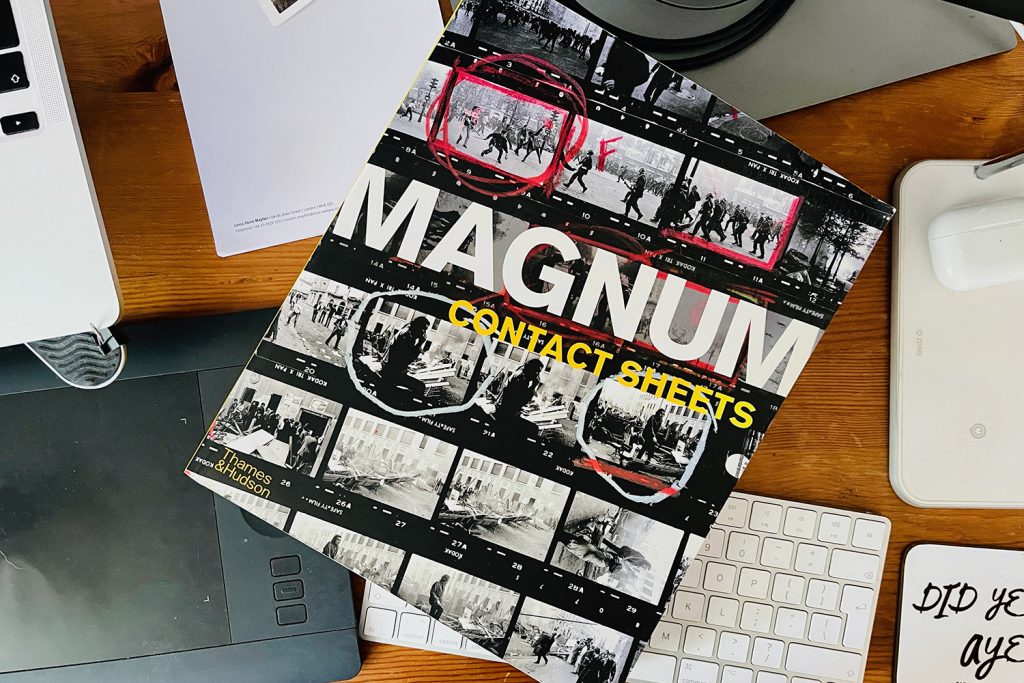

Magnum Contact Sheets (Thames and Hudson. 2011)

There is little more illustrative than the contact sheets of the masters. If fortunate, one may steal a glance at a contact sheet or three during a practical workshop or masterclass, and come to understand the process that led from the initial glimmer-spark of an idea through to the final, masterful frame. Realising this may offer fascination to both readers and practicing photographers alike, Magnum conceived of the voluminous collection, Magnum Contact Sheets.

This magnificent book demystifies the process behind the creation of many of the great photographs of our time. Every photographer makes their photographs in their own way. Some make a frame and move on, economical with their film. Others may spend a roll of Tri-X on one scene, adjusting and improving until, click. They have it. Richard Kalvar, for instance, works the scene of the mirror-like street window until he makes his reflective masterstroke, choosing only one frame from the roll. Josef Koudelka photographs the Warsaw Pact invasion of Prague in 1968, a roll from which 5 will make it to his book, Invasion Prague 68. This book is essential to any photographer, especially so for those still labouring under the misapprehension that the masters make their seminal work first time, every time.

Read Magnum Contact Sheets at the OpenLibrary through the Internet Archive

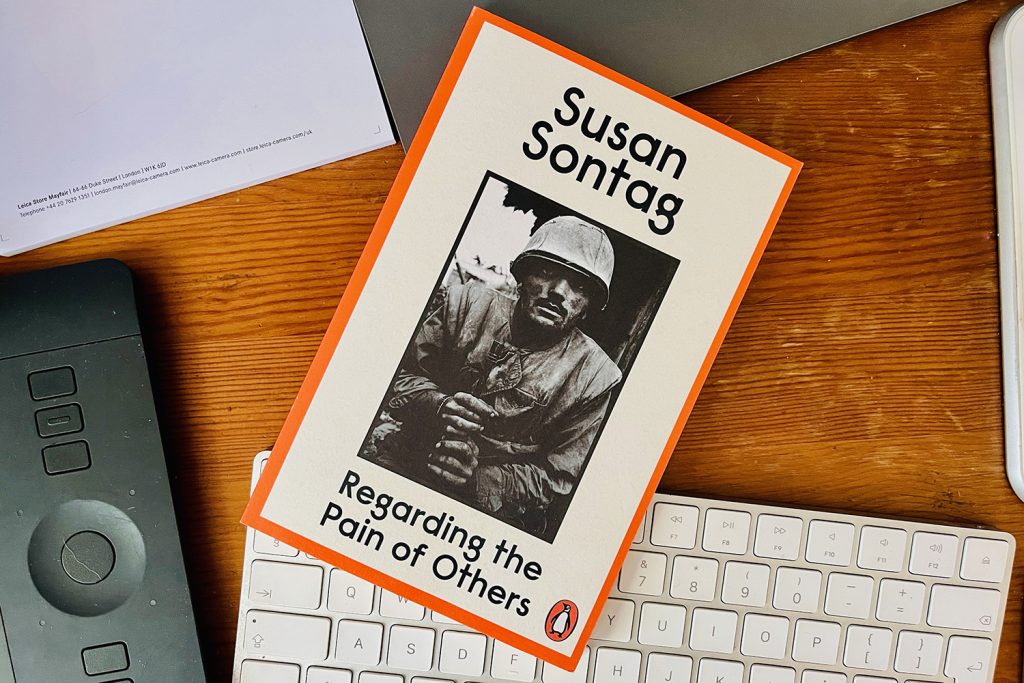

Regarding the Pain of Others – Susan Sontag (Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2003)

Moving away from the image to the written word, one might expect my choice to be Susan Sontag’s collected essays, On Photography. A reasonable expectation, and I do feel it is required reading. My choice for street photographers, though, may prove to me controversial and debatable. Nevertheless, I feel Sontag’s final book before her untimely death is more essential, although by only a hair. Sontag’s book-length essay evaluates photography as a means to represent war and violence, and in doing so attempts to answer what is the intention of depicting the atrocities of war, and how do such images affect the reader and our culture.

While less violent, the practice of street photography may still be considered to be intrusive. Interpolating these ideas reminds us that taking a photograph, while in good faith, is fundamentally a predatory act and thus there is much responsibility in pressing the shutter. The ideas presented in the book, if repositioned for our craft and considered critically, can help to understand how readers may interpret our street photography, and the conscious authorial intention behind our work. Though not to suggest I was unscrupulous before, I do feel in reading this book I became a more thoughtful, ethical, and empathetic street photographer

Read Regarding the Pain of Others at the OpenLibrary through the Internet Archive

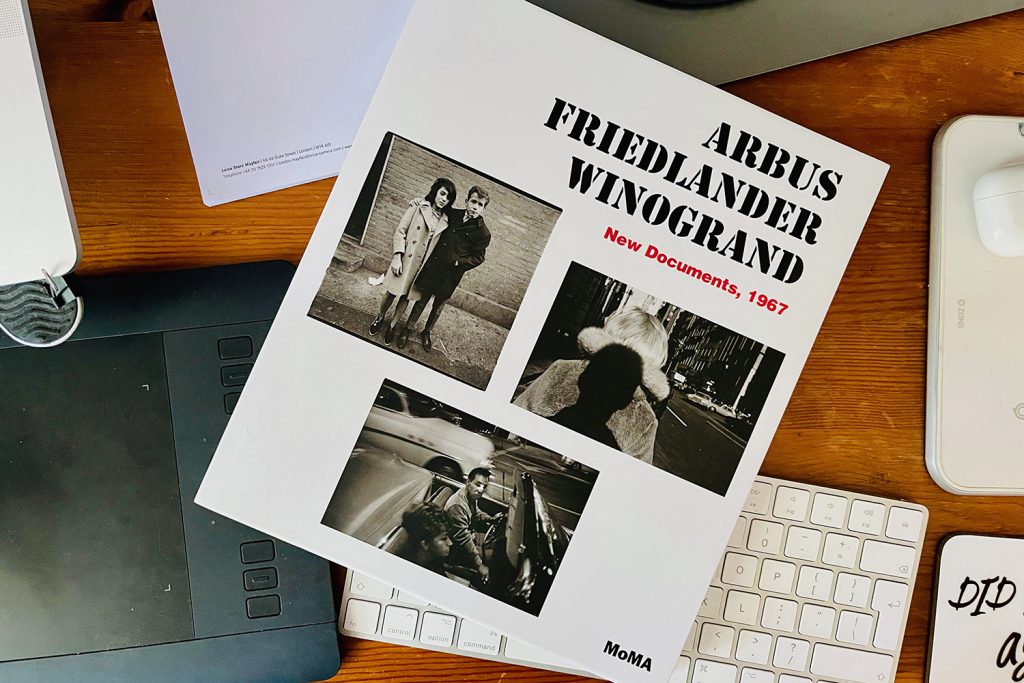

Arbus Friedlander Winogrand: New Documents, 1967 (The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 2017)

Though having developed something of a reputation as an autocrat, by his retirement in 1991, as director of photography at MoMA in New York, John Szarkowski had a radical effect on the world of art photography. One of the many exhibitions he curated in his storied career was to signal a profound shift in street photography. The exhibition was named New Documents and it comprised a selection of photographs from 3 photographers who were not widely known at the time: Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand.

What was new about New Documents? Szarkowski wrote that in the decade since The Americans was published, rather than making photographs to describe the suffering in the world in the hope it could be resolved, documentary photographers had begun to look inward, not to mend or rectify, but to know and to understand life. The central tenet of the show, and thus this book, is that in their moments captured on the street, the photographs seek to tell us more about the photographers themselves, than the world they are depicting. That the photographers are Arbus, Friedlander, and Winogrand, this becomes quite a journey to take.